Slip.

Clay particles suspended in water do nothing better—they smooth the path of your fingers across mounds of distressed earth, drawn from the ground and purified, mixed with enough sand to hold a shape and add grit. Slip, that wonderful suspension whose name steals the action from the verb, eases the way as you fight the clay, forming it beneath your fingers to find its center.

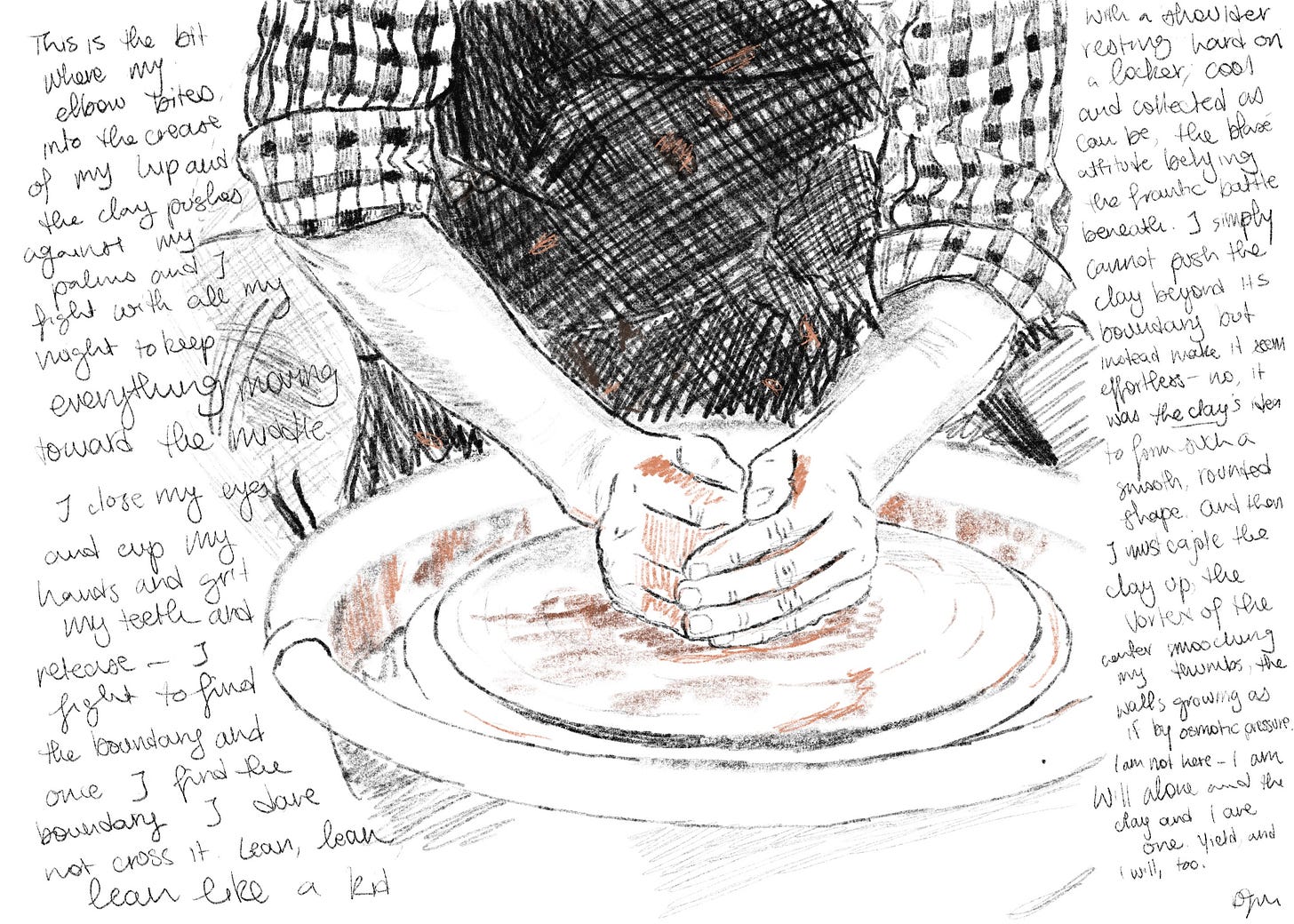

The wheel turns under my hands and I forget myself, hypnotized, suspended, focused. There is no talking while turning—at least not for me. There is no listening to music while the wheel spins, no tapping my feet. Methodical, sensual: fingers feeling wisps and lumps and topographies unseeable.

Centering is the core tenet of wheel throwing. If you can’t perfectly push your ball of clay into the eye, evenly distributed in all directions and perfectly adhered to the bat, then everything falters. There is no turning off-kilter. Any aberrant hunk of clay flies outward with more force than its fellows, pulling walls lopsided, collapsing vases into slumps, mounded folds of uneven clay piled like a discarded pair of jeans.

There is no pulling or shaping vessels from the earth without first driving them against centrifugal force, fighting all natural inclination, to meet in the middle.

And it’s difficult.

Inherently physical; feeling over thinking. I find centering easiest with my eyes closed. Knees scooped around the wheel-head and well, right elbow dug deep into the hollow near my hip, left hand supporting, guiding. The clay fights every push from my palms; my body fights every impulse to yield.

Don’t let the clay boss you around.

The clay begins to pull against my skin—left hand dips into the bucket of water, dispenses droplets from a sponge, wets the surface of the clay and forms slip again. The edge of my right palm sweeps across the bat, gathering more slip, soothing the fussy clay.

The wheel spins.

Pushing without friction, guiding without seeing. A minute or two and the ball of clay stops wobbling against my palm. The fingers of my left hand scooped around the backside of the clay—like holding a can of Coke—move in an unbroken circle.

Centered.

And there’s a litany of vocabulary, movements, that follow. Drop the hole, open the body, compress the walls and the base, pull and pull and shape and burnish. Trim and bisque and glaze and fire again. Cross your toes there’s no cracking as the clay dries, no dropped pots, no glaze stuck to the kiln or pieces welded together. Fired glaze is as hard as glass and fuses wherever it touches.

It takes over a month to shepherd a lump of clay into a finished bowl, mug, pitcher. I’ll never question the prices of handmade pieces in a seaside boutique again.

It’s no wonder pottery metaphors pepper sacred texts.

“Woe to the one who quarrels with his Maker,” Isaiah writes in chapter 45 of his book of the Bible. “An earthenware vessel among the vessels of earth! Will the clay say to the potter, ‘What are you doing?’ Or the thing you are making say, ‘He has no hands?’”

Or later, in chapter 64, Isaiah writes, “Yet you, O Lord, You are our Father; we are the clay, and You our potter, and we are all the work of Your hand.”

And much, much earlier, long before Isaiah’s time, came another line. “Shape clay into a vessel / It is the space within that makes it useful,” Lao Tzu wrote in the fifth century B.C.E.

We’ve been shaping clay, thrifted and smoothed from riverbeds and lakebeds, drawn from earth abounding with loam and sand, for millennia. The oldest pottery fragments date to 20,000 years ago, found in a cave in China.

And I picture a person—a child, maybe—dabbling in the mud when she was sent to gather water. Pulling slimy silt from the riverbed, pushing her fingers together to watch the ooze seep through, gathering it and forming a pad of mud, leaving it on a rock in the sun.

Did someone see the dried-out clay and wonder: Could this be shaped to carry water? Could it hold berries and seeds? Will it keep creatures away from the food we’ve spent so much time finding, hunting, preparing?

It’s remarkable, the way we shape the earth. We can identify pottery fragments thousands of years later, tracing itty bitty hunks back to their uses, positing full shapes from the round of a broken rim, the base of a shattered pot. Decorations and shapes indicative of unique civilizations, applications as base as holding lard to elevated creations for pouring the finest teas.

And as I sit, slip spattering my apron, my hands feeling unseen ripples and ridges, the smell of dusty silt and the rich, decaying scuzz of clay left out to cultivate critters invisible, I feel united, tethered. We are of this earth--we are shaping it under our very hands. And what love, what care, what tenderness we bring to the shapes is sealed, burnished, glazed for centuries.

How strange to think that in 20,000 years a man or woman might find a shard of the pottery I centered, pulled, fired, glazed, and fired again, and think:

For what purpose did the maker construct this? For tea, perhaps? The curve of the rounded bottom and the dainty handle suggest it must be so.

Why did she choose this motif, this color, this hint of blue on white hard-body clay? Look, she doodles leaves and stems and flowers just as I do!

And did she like her tea the same way I take mine? Two sugars and a hint of cream?

And the clay spins, separated from the mud and soil only by its association with our hands.

Thanks to Steven Ovadia, Jeremy Nguyen, Russell Smith, Lyle McKeany, Corey Wilks, and Jude Klinger for their feedback on this draft. And if you want truly amazing editors to jump in and help you edit your writing into something amazing, try out Foster! I can’t recommend this crew highly enough.

Such beautiful writing again DJ. I really enjoyed reading this.